My good friend, this week you are in luck.

For starters, I’m going to forego my usual wordy style and cut right to the chase. I’m typing this well in advance of the deadline, because I’ll be on vacation when this is posted. That means I don’t have time to blather incessantly about artwork and other such nonsense. (Really, who has the time?)

The other reason you’re in luck is because I’m about to save you about 14 months of hassling when it comes to proper time tracking. They say that good judgment comes from experience – and that experience comes from bad judgment. Well, let’s talk about my experiences with time tracking. Then we’ll get to my bad judgment near the end.

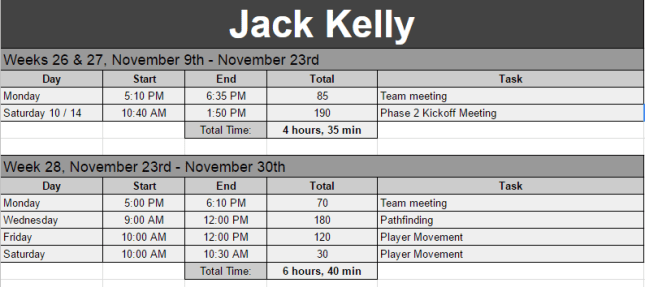

A sample time sheet from the veeeeeeery beginning of the Demo Phase.

Time Tracking: An Intro

Before we go on, a quick definition is in order. You’re probably wondering what time tracking is. (If you already know, you’ll save time by skipping this section.) Time tracking is the continuous project management process of collecting data on how members of a project are spending their time working on that project.

In theory, you’re supposed to do it for a few months and then look at the data. If you find out everyone is spending 5 times as long as they should working on some task (A), then you’ll change process (B) so that task (A) doesn’t take so long in the future. That’s the hope, anyway.

In practice, it means filling out time sheets (see above) like a madman every time you do anything related to your indie game. Done incorrectly, it will actually take time away from your project and give nothing back in return. Done properly, it gives you keen just-in-time insights that let you wisely cut features and move staff around before you hit that impending deadline.

On the surface this time sheet may look good. However, on further inspection…

How To Do A Bad Job

I want to tell you how to do time tracking properly, but you won’t appreciate the correct approach until you see it done wrong.

For the entirety of our time working on the Where Shadows Slumber Demo, Jack and I tracked our time with a time sheet I devised. This Google Spreadsheet had an entry for every sprint (a period of 1 or 2 weeks, usually the time between team Skype meetings) with a bunch of headings: Day, Start, End, Total, and Task. Here’s what they meant:

- Day – What day during the Sprint did you work on this Task?

- Start – “Punch in” at a time to begin working on the Task.

- End – “Punch out” at a time to stop working on the Task.

- Total – The number of minutes you worked on the Task.

- Task – What you worked on.

As you can see, this tells us a lot about how I spent my Sprint. But none of this information is relevant to project management in the long term. There’s no indication whether or not I actually completed the Tasks I worked on. (Some have percent complete markers, but those are just guesses anyway) Looking at this, I have no idea how the project moved ahead during the Sprint. Our only real metric is the number of hours I worked – nearly 19. But… who cares? It’s not like I’m charging anyone by the hour! Jack and I do this as a labor of love, with salaries to come from proceeds from the final game.

This time sheet makes the critical error of measuring the wrong metric. I must confess that some weeks, I tried to just work for a long time instead of working effectively so I could feel good about logging impressive hours. That’s a sign of bad project management. As a manager, you ought to offer incentives for behavior that gets the project completed on-time and at a high quality.

The results? Internally, we had a lot of arguments about this process as Jack felt it was unnecessary. Because I never returned to the data we created to analyze it, we got nothing for all our tedious efforts. Jack stopped tracking his time, and that was a warning sign that I needed to change things up. Our time tracking was costing us time to do, with no benefit to the team. Time for a change!

Time Sheet: Version 2.0!

My Time Tracking Strategy

Here’s how I altered the process for the final project. Starting April 4th, I began tracking my time the way shown above. The headings this time are Task, EST, ACT, Error, and Status. Let’s deconstruct that jargon:

- Task – One entry for the Task this time, no matter how long it takes.

- EST – Short for “Estimate”, this is an educated guess about how many minutes this task will take to complete. You’re supposed to guess at the beginning of the sprint.

- ACT – Short for “Actual”, this is the actual number of minutes this task took to complete. You’re supposed to fill this in as you go. It’s the only thing that requires active time tracking while you work.

- Error – This is automatically calculated with an Excel formula. It’s the percentage of error between your guess (EST) and the actual time (ACT). You want to get 0%, meaning that your guess was perfect. The larger the number is, the worse your guess was. The formula I use here is =(ACT – EST ) / ACT.

- Status – The most important part! Each task is a discrete item within the larger project that is either done or not done. We want a full list of check marks at the end of this sprint. If a task is left incomplete, there had better be a good reason!

As you can see, now the spreadsheet is setup with the Task as the most important thing. We’re measuring whether tasks are complete ( ✔ ) or incomplete ( X ) instead of measuring how many hours someone has worked. That’s important, because people tend to maximize whatever they’re being graded on if you observe them working.

It’s changing my behavior, too! Instead of acting like I need to fill my time sheet with useless “minute points”, now I feel the pressure to get my estimation right. Of course, I can only be right if I finish the Task. The incentive structure of this time sheet is way better! We begin with an incentive to make a good guess. Then we have an incentive to conform towards that good guess so we don’t get “mark of shame error percentages”. Finally, we have an incentive to finish each Task so it doesn’t remain a permanent “X of shame” forever. Perfect!

This will lead to actual progress on the project and helpful information about our estimation ability at a glance.

In all seriousness, though – I did fail.

The Lesson? Get It Right The First Time

To conclude… I have bad news. If you’re a project manager, listen up! You need to get this stuff right the first time. Putting your teammates through a tedious process of time tracking gets on their nerves after a while. People can only put up with that for so long, especially if they don’t get anything out of it.

I’m still doing time tracking, but Jack has become disillusioned with the process. I don’t blame him, but it’s still a shame. Had I gotten this right the first time, we might still be on the same page.

Don’t reinvent the wheel like I did on my first attempt. Use a proven method that works, read some software management books, talk to an industry professional, and communicate with your teammates during the early stages of the project. If you do, people will find time tracking fulfilling. Otherwise, they’ll fall by the wayside. And remember – you can never force anyone to do anything, you can only offer irresistible incentives!

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Thanks for taking the “time” to read this “clock”. Have a question about time tracking that was not answered here? You can find out more about our game at WhereShadowsSlumber.com, ask us on Twitter (@GameRevenant), Facebook, itch.io, or Twitch, and feel free to email us directly at contact@GameRevenant.com.

Frank DiCola is the founder of Game Revenant and the artist for Where Shadows Slumber.