This week marks the deployment of our first batch of test levels, assuming I haven’t totally screwed up and delayed them. Throughout the past few months, we’ve been building a list of testers, and it is finally time to put it to good use!

If you’re on the list and you have an iOS device, you should have received an invitation to our TestFlight over the weekend. If you’re on Android, you can expect a similar email later this week. If you’re not on the list (or don’t know if you are), just let us know! We haven’t hit the limit on testers yet, and every pair of eyes helps us make a better game.

Frank already wrote about our testing, and why we’re doing it. This post touches on a lot of the same things, but I want to delve a little bit more into the benefits of testing.

Mommy, look what I made!

A child returns home, an exuberant look on her face. “Mommy, look what I made!” she exclaims, holding up a piece of construction paper covered in marker lines and dried macaroni. Her mother reaches down and takes the paper. “Isn’t it great?”

“Why, yes, darling, it’s the most beautiful piece of art I’ve ever seen!”

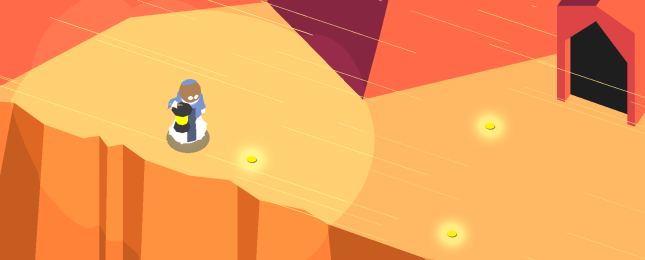

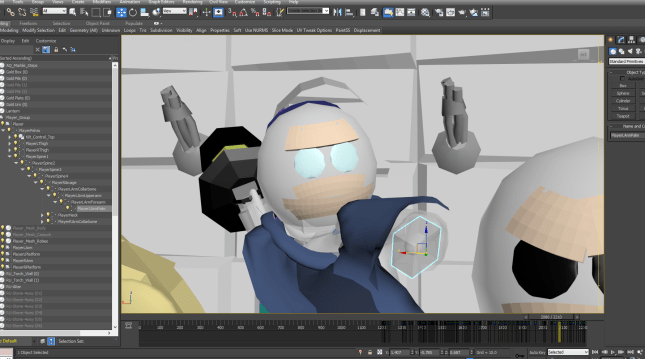

The original concept art Frank made for Where Shadows Slumber

Now, you and I know that the mother in this story is not telling the truth. Obviously, Where Shadows Slumber is the most beautiful piece of art she’s ever seen. But her daughter doesn’t know that – her daughter planned out the art, decided exactly how she would approach the task, and executed flawlessly.

Frank and I are the daughter in this metaphor, and Where Shadows Slumber is the macaroni masterpiece. We look at our game and we see something beautiful – but who knows what it actually looks like?

You do! You, our adoring public, are our mother. However, we need you to tell us the truth! We will never grow up to be a wonderful artist if you tell us that our macaroni levels are beautifully designed when they’re not.

This is the concept behind a lot of what we have been doing over the past year. We created a demo for the sole purpose of showing it to people and getting feedback about the game. We’re sending out test levels to get feedback about our level design. We even write this blog, in part, to get feedback about our process!

We use all of this feedback to help make Where Shadows Slumber a better game. That is the benefit of testing.

The Power of the POC

If you’re a game developer, and your friends and family know you’re a game developer, then there is a phenomenon I’m sure you’re quite familiar with. If not, allow me to explain.

Most people don’t understand the amount of time and effort that goes into the development of a game. Therefore, if someone thinks of a half-decent game idea, they come to you with it. If I had a dollar for every time someone has said “Jack, listen to this idea for a game – you’ll be a millionaire!”, I actually would be a millionaire.

So, you end with a lot more game ideas then you can possibly make. Some of them might actually be pretty good, but you’re just one person – how can you tell if an idea will end up working out? Do you have to just pick a concept, make the whole game, and then just hope that people like it?

This is exactly what proof of concept projects are for! Can you imagine if we had spent two years making the full game for Where Shadows Slumber, only to release it and find out that nobody enjoys shadow-based puzzles? What a waste! But spending two months working on a project that could become something big is totally worth it, even if people don’t like it.

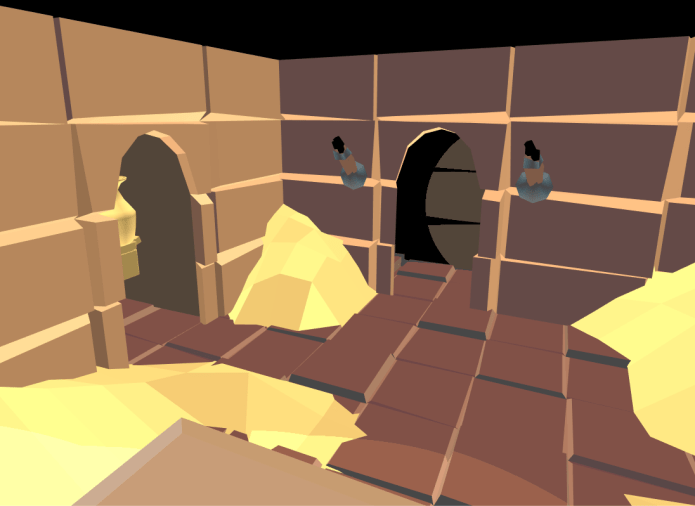

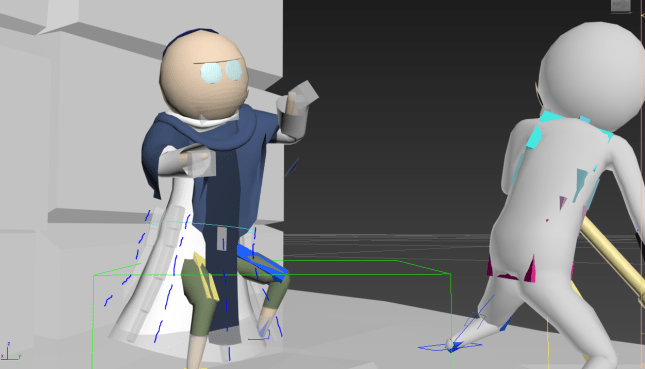

A shot from one of our earliest POCs

That’s exactly how Where Shadows Slumber started. I came up with the idea, and I immediately spent two months or so developing a POC, a very, very basic version of the game, that would just be used to tell if the game had any merit. I showed it to Frank and a few other friends, and they liked it, so we decided to make the full game. If they hadn’t liked it, then we would have scrapped the project. I would have wasted two months, but I would have known that it was a project not worth pursuing, without wasting even more time.

Testing Design

In my opinion, the hardest part of game development is design. Programming is easy enough, once you know what you want to program. Art, on the other hand, would be the hardest part if it weren’t for Frank, but that’s just because I’m bad at art.

Once you know what you want to make, programming and art are mostly execution on that vision. Coming up with that vision is the hard part. What is your game mechanic? How does it work? How do you explain how it works to the player? What does your difficulty curve look like? On and on, there are thousands of questions like this that you can apply to game design, and they’re all important.

This is one of the main reasons we try to get as many people as possible to play our game. There are certain realizations about design that you can only get by showing it to a lot of people and getting feedback. We never would have discovered how much people dislike ‘randomness’, which is something that could have played a major part in our game, if we hadn’t shown it to a bunch of people.

But even once you’ve made all of the decisions regarding your game’s mechanics, you still need that feedback on the last giant piece of the game design puzzle: level design. If you have an awesome mechanic, but your levels are boring and easy, or way too hard, nobody’s gonna want to play.

In order to prevent this, we’re doing some alpha testing! We have all of the levels designed, and we have all of the mechanics half-implemented, so we’re sending out test levels!

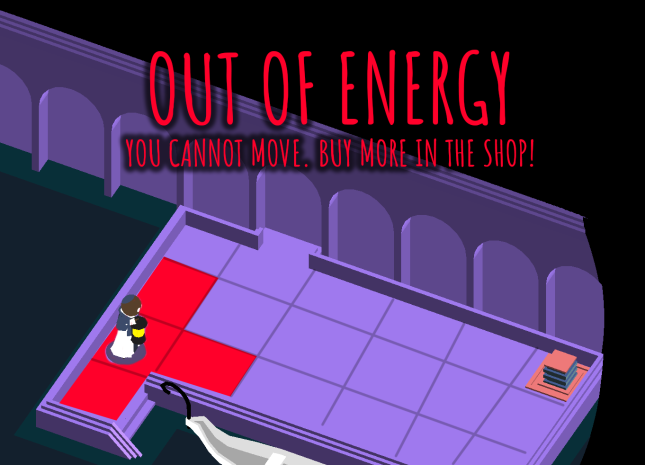

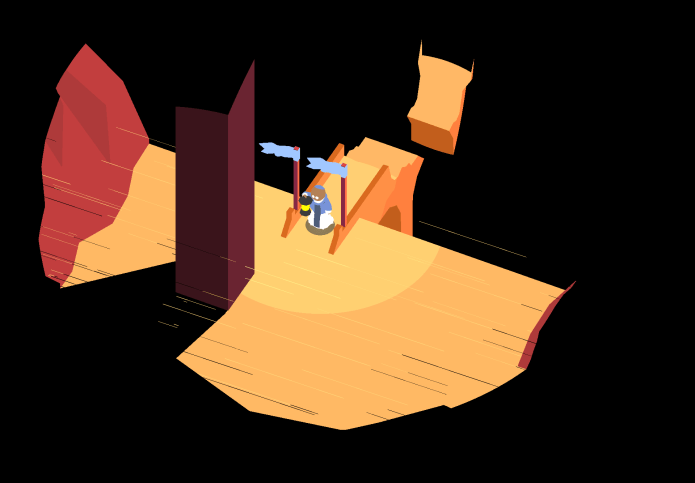

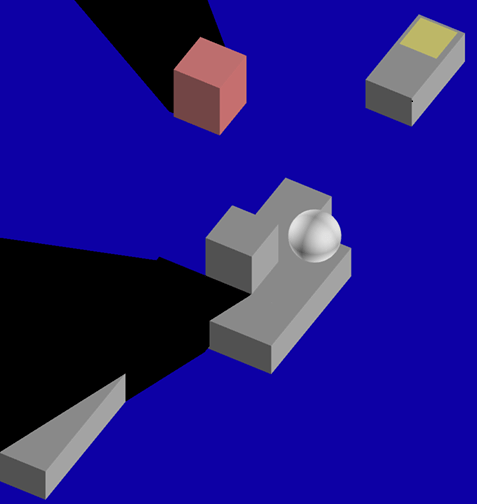

This is what it would look like if I were in charge of the art…

These levels are ugly – but we’re not testing the art! These levels are buggy – but we’re not testing the code! These levels just might be poorly-designed, and that’s what we want to know. Our testers will tell us what they like and don’t like about these levels, and we will update them accordingly.

The important part of this process is that it’s happening as early as possible. If we sent out fully-complete levels, and then we had to change one, we would end up either scrapping the art, which is a huge waste, or trying to change the level without changing the art, which just makes it look weird. That’s why these levels look all dull – it’s all part of the plan!

Testing Philosophy

The last thing you want is to work hard for two years on a project, only to release it and find that it’s not as great as you thought it was. In particular, no matter how great you think it is, your audience might not enjoy it. While there will always be people that don’t like your game, it’s important to make sure that your target audience does like it. And how do you ensure that will happen? Testing!

It’s not a great experience to hear someone say they don’t like your game, and it’s perfectly natural to shy away from that. However, hearing that from a dozen people and still having time to make changes is a whole lot better than hearing it from a thousand people after you’ve already released the game.

Whether it be unit tests (small tests to make sure that one part of your code works) or beta testing (sending an almost-complete game out to fans to look for small bugs and last-minute fixes), testing is an important part of development. Don’t get caught up in your own little game-dev world; make sure you find out what the people want!

As always, let us know if you have any questions or comments about testing (or anything else)! You can always find out more about our game at WhereShadowsSlumber.com, find us on Twitter (@GameRevenant), Facebook, itch.io, or Twitch, and feel free to email us directly with any questions or feedback at contact@GameRevenant.com.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Jack Kelly is the head developer and designer for Where Shadows Slumber.